Post-arrest patients with more significant reperfusion injury (for example, Pittsburgh Cardiac Arrest Category (PCAC) greater than or equal to 3, revised post-Cardiac Arrest Syndrome for Therapeutic hypothermia score (rCAST) greater than 6, evidence of shock, and/or longer arrest times) may benefit from mild hypothermia to 33 degrees Celsius, while less severe post-arrest patients may benefit from fever prevention at less than 37.5 degrees Celsius.

Targeted temperature management (TTM) for patients following cardiac arrest resuscitation has gone through several dosing iterations in the past two decades. Early work on TTM in 2002 showed benefit to cooling to 33 degrees Celsius, which subsequently influenced international resuscitation guidelines to recommend mild hypothermia at 32 degrees to 34 degrees Celsius in 2005.1,2 However, the European TTM1 trial in 2013 showed similar outcomes for those cooled to 33 degrees Celsius compared to 36 degrees Celsius, leading to a 2015 AHA class I recommendation of “cooling between 32 degrees Celsius-36 degrees Celsius.”3,4 The Hyperion trial in 2019 demonstrated that TTM at 33 degrees Celsius was efficacious for non-shockable rhythms, reinforcing the guidelines recommendation for post-arrest TTM.5,6

In 2021, the TTM2 trial was published. TTM2 was a multicenter, randomized trial that enrolled 1850 OHCA patients and randomized them to 33 degrees Celsius or normothermia. Patients were maintained at their assigned target temperatures for 28 hours and then maintained at normothermia less than 37.5 degrees Celsius for 72 hours. Outcomes, including survival at 6 months and neurologic outcome, between the two groups were not clinically or statistically different, but the hypothermia group had a higher incidence of hemodynamically compromising arrythmias (24 percent versus 17 percent in the normothermia group; RR 1.45 (1.21–1.75).

Click to enlarge.

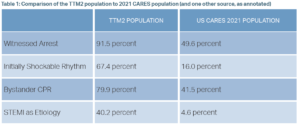

The TTM2 trial, while rigorously performed, has important limitations to generalizability for the US patient population. TTM2 primarily enrolled patients in Northern Europe and thus had a number of characteristics not seen in the U.S. As seen in Table 1, the TTM2 population had markedly more favorable prevalence of positive prognosticators of arrest, compared to an American population from the same year.7 TTM2 is generally interpreted as favoring normothermia for post-arrest care, but the question is whether this trial is broadly applicable to many countries with less developed community CPR involvement.

In August 2023, the American Heart Association and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation published a scientific advisory that derived three conclusions.8,9 First, based on TTM2, they recommend that cooling OHCA patients of cardiac or unknown cause, excluding those with unwitnessed asystole, to less than 37.5 degrees Celsius “is a reasonable and evidence-based approach.” Second, as TTM2 did not address in-hospital cardiac arrest or OHCA of noncardiac (other medical) cause, the guidelines remain essentially equivocal as to “whether some of these patients might benefit from temperature control at temperatures between 33 degrees C and 37.5 degrees C.” Finally, the guidelines support active temperature management’s (though not necessarily hypothermia) role in improving post-arrest outcomes. This is best demonstrated by the TTM2 data showing that 46 percent of patients in the normothermia group required active cooling, on top of pharmacological antipyresis.

The accumulated post-arrest care literature makes clear that careful fever avoidance following resuscitation is essential. But the question remains, is there ever an explicit indication for hypothermia to 33 degrees Celsius, based on the earlier trials and the strong laboratory evidence supporting this more aggressive form of temperature control? Growing evidence suggests that there may be utility for TTM in the sicker phenotype of arrest patients. Several recent studies yield insights into this hypothesis:

In a single site retrospective cohort study, Callaway et al demonstrated that TTM efficacy may be impacted by arrest severity.10 In this observational study of 911 American post-arrest patients, sicker patients (PCAC greater than or equal to 3) had improved outcomes when treated at 33 degrees Celsius while less sick patients (PCAC less than or equal to 2) had better outcomes when treated at 36 degrees Celsius. This finding is consistent with the large animal model literature on post-arrest TTM, where a dose effect relationship of TTM is related to arrest model severity.

In a multisite retrospective cohort study, a study by Nishikimi, et al., adds to the hypothesis that TTM efficacy is dependent on arrest severity.11 Similar to the Callaway study, this study of 1,111 Japanese patients replicated the finding that low-severity post-arrest patients did not benefit from hypothermia while patients with moderate-severity arrests significantly benefited from hypothermia. Adding nuance, this study also showed that the highest-severity arrests did not benefit from hypothermia. While TTM may attenuate injury, it does not reverse it, so it is unsurprising to discover a profoundly injured subset of patients who do not benefit from TTM. In summary, this study shows that there is a subset of post-arrest patients who experience neither too much, nor too little injury and are therefore disposed to benefit from expeditious hypothermic intervention.

Several studies have shown that after TTM1 (2013), in cases where hospitals changed post-arrest temperature targets from 33 degrees Celsius to 36 degrees Celsius, patients had an concomitant increase in fever, poor neurological outcomes and increased mortality.12–13 These are challenging studies to draw definitive conclusions from, however they suggest that some of these post-TTM1 patients who were cooled to 36 degrees Celsius did worse, supporting the notion that there exists a subset of patients who benefit from cooling to 33 degrees Celsius.

There is a current vigorous debate regarding post-arrest TTM. Who should receive it? At what dose? For how long? There are a number of trials in progress that may help address these questions; notably, ICECAP, IH-TTM, and PRINCESS-2, each focusing on different aspects of TTM dosing and timing. Until then, we propose that it’s worth considering mild hypothermia (33 degrees Celsius) in our sickest post-arrest patients, while avoiding fever in every patient resuscitated from cardiac arrest.

Dr. Abella is the William G. Baxt professor of emergency medicine and vice chair for research in the department of emergency medicine and the director of the center for resuscitation science at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Abella is the William G. Baxt professor of emergency medicine and vice chair for research in the department of emergency medicine and the director of the center for resuscitation science at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Reis is a PGY2 resident in the department of emergency medicine and a member of the center for resuscitation science at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Reis is a PGY2 resident in the department of emergency medicine and a member of the center for resuscitation science at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest (published correction appears in N Engl J Med 2002;346(22):1756). N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549-56.

- Group W, Nolan JP, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003;108(1):118-21.

- Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33°C versus 36°C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197-206.

- Andersen LW, Berg KM, et al. Temperature management after cardiac arrest an advisory statement by the advanced life support task force of the international liaison committee on resuscitation and the American Heart Association emergency cardiovascular care committee and the council on cardiopulmonary, critical care, perioperative and resuscitation. Circulation. 2015;132(25):2448-56.

- Lascarrou J-B, Merdji H, et al. Targeted temperature management for cardiac arrest with nonshockable rhythm. N Engl J Med. October 2019;381(24):2327-37.

- Soar J, Berg KM, et al. Adult advanced life support: 2020 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Resuscitation. 2020;156:A80-A119.

- CARES Annual Report. Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival website. https://mycares.net/sitepages/uploads/2022/2021_flipbook/index.html?page=1. Accessed March 26, 2024.

- Tran AT, Hart AJ, et al. A risk-adjustment model for patients presenting to hospitals with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Resuscitation. 2022;171:41-47.

- Perman SM, Bartos JA, et al. Temperature management for comatose adult survivors of cardiac arrest: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148(12):982-8.

- Callaway CW, Coppler PJ, et al. Association of initial illness severity and outcomes after cardiac arrest with targeted temperature management at 36 °C or 33 °C. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e208215-e208215.

- Nishikimi M, Ogura T, et al. Outcome related to level of targeted temperature management in postcardiac arrest syndrome of low, moderate, and high severities: a nationwide multicenter prospective registry. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(8):E741-50.

- Nolan JP, Orzechowska I, et al. Changes in temperature management and outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in United Kingdom intensive care units following publication of the targeted temperature management trial. Resuscitation.2021;162:304-311.

- Johnson NJ, Danielson KR, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33 versus 36 degrees: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(3):362-9.

- Bray JE, Stub D, et al. Changing target temperature from 33 °C to 36 °C in the ICU management of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A before and after study. Resuscitation. 2017;113:39-43.