A 39-year-old male presents to your emergency department (ED) with complaints of a headache after a roll-over motor vehicle accident. He was a restrained driver traveling 65 miles per hour on the highway when he lost control in the rain, hit a guardrail, and had a brief loss of consciousness. His only medical history is hypertension and does not take any anticoagulation. He has a normal neurological exam with a glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 15. Due to the mechanism of injury, a head CT was obtained. The patient was found to have a small intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Neurosurgery was consulted at the regional trauma center where the consultant recommended observing the patient in the ED with a repeat head CT in six hours. Should you do it or should you look for another transferring facility?

Patients who are found to have traumatic intracranial hemorrhages (tICHs) are frequently transferred for neurosurgical evaluation.1,2 Patients with isolated mild tICH typically do not experience neurological deterioration nor undergo neurosurgical intervention. The vast majority of mild tICH patients can be discharged within 24 hours including from the ED.1 Transferring these patients can lead to unnecessary costs, strain on the health care system, and inconvenience to patients and families who have to travel far distances without accruing any added benefit. Unnecessary transfers can also worsen bed shortages, lead to emergency department crowding, and worsen hospital boarding at trauma centers. This ultimately delays care for other patients who may benefit from a transfer. Recent studies have started to look at identifying patients with an isolated tICH who do not need intensive monitoring or intervention and could be discharged from the ED after a short period of observation.

Click to enlarge.

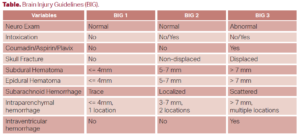

Several tools have been evaluated to risk stratify patients with mild tICHs for deterioration and neurosurgical intervention. The first is the Brain Injury Guidelines (BIG), which looked at various factors to risk stratify patients into three categories (see Table). In their multi-center validation study of 2033 patients, they found that patients who were classified as BIG 1 and BIG 2 (around 30 percent of all patients) had zero TBI-related post-discharge ED visits or 30-day readmissions. BIG 1 patients (around 15 percent of patients) also did not require repeat neuroimaging or neurosurgical consultation. They were discharged from the ED after only six hours of observation.3

The SafeSDH tool defined low risk patients as those who had none of the following: taking anticoagulation or clopidogrel, more than one discrete type of hematoma, subdural hematoma (SDH) greater than 5 mm, midline shift, and GCS less than 14. The primary composite outcome included not only the need for neurosurgical intervention (both immediate and delayed), but also any neurological decline and death. In a validation study of 753 patients at 6 hospitals (including both trauma and non-trauma centers), 21.5 percent of patients were deemed low risk. Sensitivity of the tool was 99 percent and a negative predictive value of 0.03. Only two cases fell out due to neurological decline which were felt to be related to medical reasons and not from the SDH. Repeat neuroimaging showed no change in the size of the SDH and no neurosurgical intervention was required.1

Other studies utilizing ED observation pathways have been shown to safely discharge patients home without the need for an admission to the hospital.4,5 Multidisciplinary teams involving neurosurgery, trauma, and emergency medicine can create pathways for isolated tICH that do not require admission or transfer. A phased approach can be used starting with a protocol like BIG and having neurosurgery review images for all patients with tICH. In the authors’ experience of more than 120 patients at several community sites, no unexpected adverse outcomes have been seen over the last two years. While local validation is important, safely reducing unnecessary transfers and admissions can not only reduce costs and inconvenience to the patient, it also helps referral centers that struggle with capacity.

You decided to take the consultant’s recommendation and while waiting for the repeat CT, read this ACEP Now article on the practicality of discharging tICH from the ED. Six hours later, the repeat CT head showed no difference in the size of the hemorrhage. Your patient’s neurologic exam remained unchanged. After discussing with neurosurgery again, they recommended discharge and you felt comfortable and in agreement.

Dr. Lo is the chief of emergency medicine at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital and professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School. He is a partner at Emergency Physicians of Tidewater, a private, democratic group in Norfolk, Virginia.

Dr. Lo is the chief of emergency medicine at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital and professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School. He is a partner at Emergency Physicians of Tidewater, a private, democratic group in Norfolk, Virginia.

Dr. Weingart is the assistant medical director at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital emergency department and an assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School. He is a partner at Emergency Physicians of Tidewater.

Dr. Weingart is the assistant medical director at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital emergency department and an assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School. He is a partner at Emergency Physicians of Tidewater.

Dr. Gartman is an education fellow and Instructor at Eastern Virginia Medical School department of emergency medicine in Norfolk, Virginia.

Dr. Gartman is an education fellow and Instructor at Eastern Virginia Medical School department of emergency medicine in Norfolk, Virginia.

- Borczuk P, Van Ornam J, Yun BJ, et al. Rapid discharge after interfacility transfer for mild traumatic intracranial hemorrhage: frequency and associated factors. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(2):307-315.

- Pruitt P, Castillo R, Rogers A, et al. External Validation of a Tool to Identify Low-Risk Patients With Isolated Subdural Hematoma and Preserved Consciousness. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;18:S0196-0644(23)01138-1. Epub ahead of print.

- Joseph B, Obaid O, Dultz L, et al. Validating the Brain Injury Guidelines: Results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma prospective multi-institutional trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93(2):157-165.

- Singleton JM, Bilello LA, Greige T, et al. Outcomes of a novel ED observation pathway for mild traumatic brain injury and associated intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;45:340-344.

- Wheatley MA, Kapil S, Lewis A, O’Sullivan JW, Armentrout J, Moran TP, Osborne A, Moore BL, Morse B, Rhee P, Ahmad F, Atallah H. Management of Minor Traumatic Brain Injury in an ED Observation Unit. West J Emerg Med. 2021;15(4):943-950.